At the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, 1992, the rapidly expanding global trade in chemicals was highlighted for posing unnecessary risk to both people and the environment, due to the wide assortment of national and regional chemical hazard classification systems in use at that time. Chemical classifications that might be understood perfectly well by an exporter may be completely misinterpreted by an importer, resulting in avoidable exposure to hazardous material. Subsequently, the United Nations sought to reduce this risk by implementing a unified system which could be understood globally, thereby reforming safety, and consequently easing trade.

The Globally Harmonised System for classification and labelling of chemicals (GHS) is the UN’s solution to this issue. The first version of GHS was published in 2003, laying out both how chemicals should be classified, as well as the format for communicating those classifications via Safety Data Sheets (SDS) and Labelling. Though the primary audience for GHS is regulatory bodies and professionals, the information communicated is clear enough to be understood by members of the general public. The visual nature of the system also helps to communicate through easily interpreted symbols, smoothing out language and literacy barriers.

GHS lays out various hazard types, across the three areas of Physical, Health and Environmental. Parameters are laid down for categorising severity, with Category 1 being most severe. Methods are also detailed for calculating classifications for complex chemical mixtures lacking specific test data. Each classification is given the following information to convey exposure mitigation:

- A hazard statement (eg. H301 –Toxic if swallowed)

- A hazard pictogram (a red-bordered diamond)

- Associated precautionary statements (eg. P331 – Do not induce vomiting)

The architecture behind the GHS system is similar to that of the outgoing EU legislation, and aligns closely with UN Dangerous Goods (DG) regulations. However, DG and GHS place emphasis on different hazards: DG does not consider, for example, long-term exposure to hazards such as CMRs (carcinogen – mutagen – reproductive toxin); and GHS does not consider non-chemical hazards such as lithium batteries, radioactivity or biohazards, which are necessary considerations for transport.

GHS is a non-legally binding agreement rather than a formal treaty, and to date, almost all countries have implemented GHS into law. In the EU, GHS was phased in from 2008 as the CLP (Classification, Labelling and Packaging) Regulation. The downfall of GHS is that legislatures are free to adopt various GHS ‘building blocks’, with the result that what should be ‘globally harmonised’, isn’t! For example, in the EU the least harmful Acute Toxicity (category 5) is not used; many legislations haven’t adopted the least hazardous Flammable Liquid category, combustible (category 4); and in the USA, environmental hazards are dealt with separately.

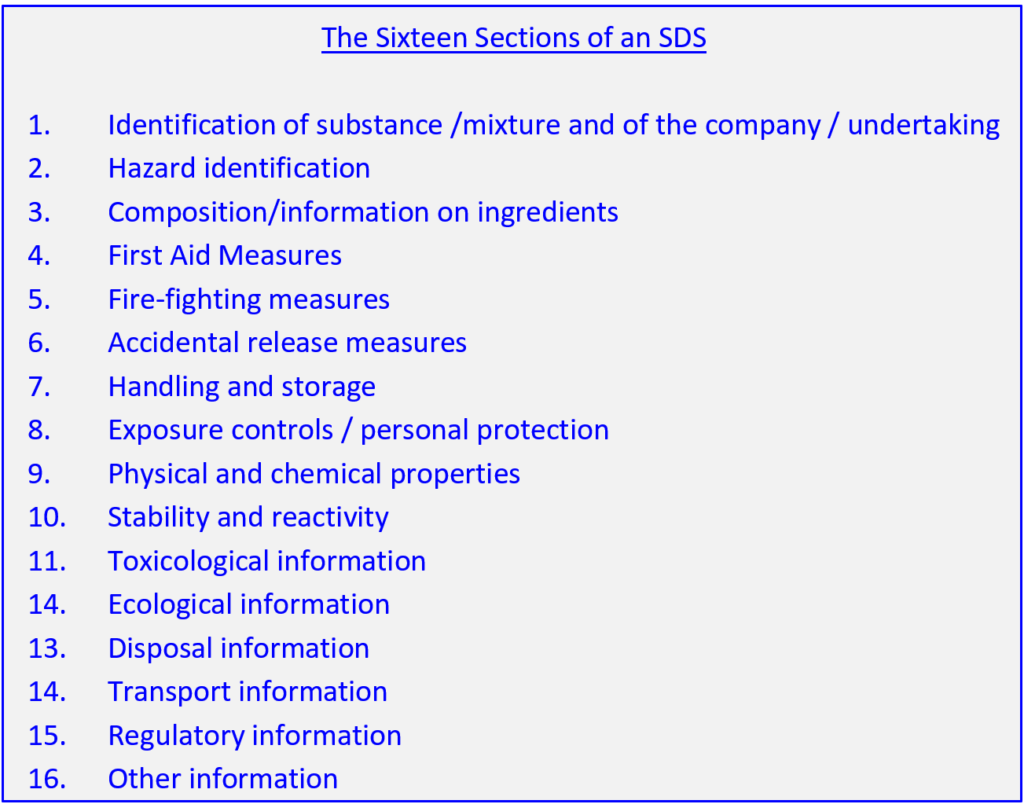

Information is communicated to end-users, distributors, shipping agents, vendors, emergency services, and anyone else who might need to know, via the SDS and product label. The label conveys information for immediate use, including the hazards and precautions, along with emergency contact details. The SDS is a detailed document, set out in sixteen sections, all of which are intrinsically linked to the hazard classification in Section 2.

For example, a highly flammable liquid should have corresponding flash-point and boiling point in section 9, and appropriate storage and fire-fighting measures, while a skin irritant should have relevant first aid measures, and advice on PPE. Transport information is given in Section 14, with the DG classification for necessary modes of transport.

Generally, suppliers (be they manufacturer, distributor or vendor) must provide an SDS to the downstream customer, in order to make informed decisions. Does the chemical corrode pipework? Irritate skin? Kill fish? All valuable considerations when establishing application suitability, compiling a COSHH assessment, or arranging disposal. Incorrectly classified chemical products and non-compliant SDSs can result in property damage, personal injury and pollution. Whilst an SDS can’t forewarn of all eventualities, known incompatibilities which might be otherwise considered normal should be detailed; for example, Hawkins has investigated cases of calcium oxide, used as a disinfectant in agricultural settings, causing fires when wetted.

In forensic investigation, the SDS is useful in establishing that a product has been used in a proper and appropriate manner. If information within the SDS is incorrect, there may be a case against the manufacturer or SDS author. The ‘requirement to provide’ an SDS also effectively transfers the onus of mitigating an incident. In the domestic market, sufficient information is usually found on the product label and SDSs are not automatically provided, but if you request one to accompany your bleach or white spirit, it must be provided by the vendor. Without the most up-to-date information being provided with the goods, the handler (be they shipping agent, distributor, or end-user) is ill-prepared; culpability for any incidents then passes up the supply chain.

Hawkins can offer expertise establishing where the information chain has failed. We can review safety documentation for accuracy, and dissect the supply chain to establish culpability. We can review safe practices, and attend scenes where chemicals are suspected of involvement. We have offices throughout the UK, and Dubai, Hong Kong and Singapore, and can mobilise quickly to visit courier depots or ports where GHS and DG regulations collide.

It’s without doubt that GHS has reduced the risks from chemicals. Nearly all countries have adopted some form of GHS, and the legislation laid out means suppliers into the domestic market take much more care with their product design; and at the opposite end of the scale, manufacturers and shippers are more aware of the consequences of misuse. Unscrupulous operators at both ends of the scale will always exist, but with GHS and the aligned DG regulations there will be fewer places to hide.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

James Morris has nearly two decades experience working in laboratories. He has worked as a Product Steward for global petrochemicals companies, and is a qualified DGSA. Since joining Hawkins, James has investigated fires, chemical explosions, and road and sea transport incidents.