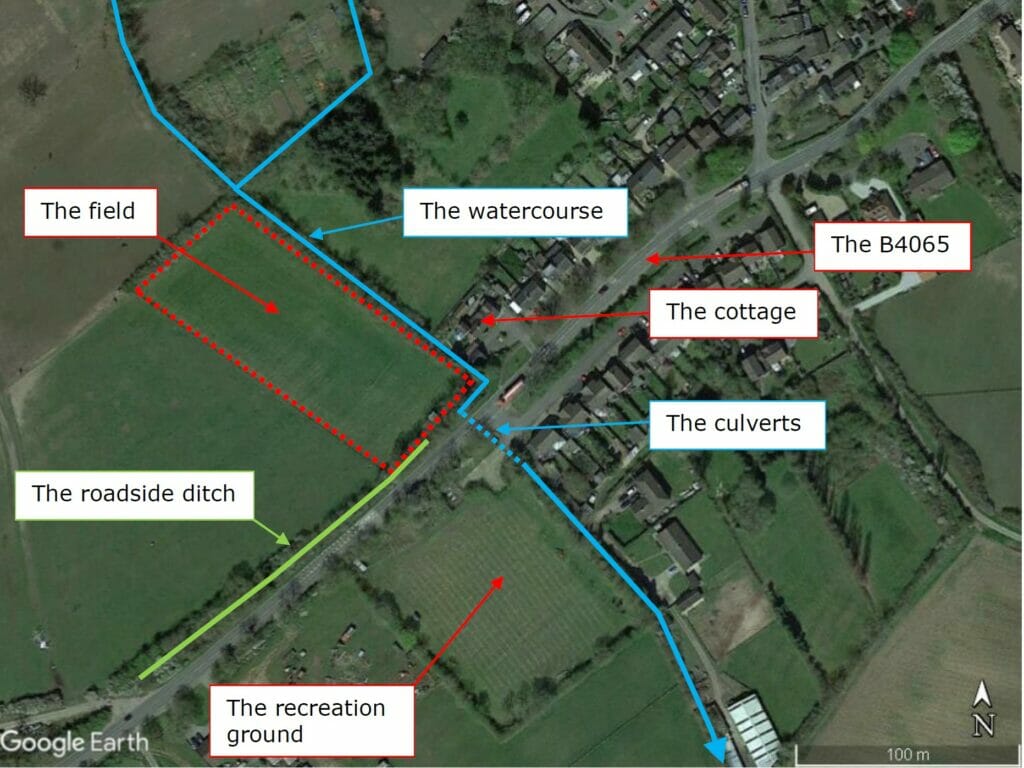

In the case of Tayton and Tayton -v- (1) Warwickshire County Council and (2) Rugby Borough Council, the Taytons (the Claimants) purchased Brookside Cottage and a neighbouring field in 2013, with the intention of building a small housing development on the field. A watercourse flows in a southerly direction along the eastern boundary of the field, and thereafter through two highway culverts, as indicated in the plan below. The Taytons submitted a planning application to develop the field in 2016, but this was refused by Rugby Borough Council (the local planning authority) for several reasons; one of which was in relation to the risk of flooding. They submitted a second planning application but this was also refused and a subsequent appeal was dismissed.

The first of the two culverts is owned by Warwickshire County Council; although the Claimants alleged that Rugby Borough Council owned the second culvert, Rugby Borough Council disputed this. The Claimants alleged that the risk of flooding arose because both culverts had insufficient capacity, which they also claimed had caused the field to flood on several occasions. They brought a claim in nuisance against both councils; the claim included the cost of a flood management scheme and lost profit on the proposed development. They also sought an injunction to require the councils to enlarge the culverts (at a likely cost of more than £300,000 to Warwickshire County Council alone), based on established principles set out in Bybrook Barn Garden Centre -v- Kent County Council [2001]. Weightmans solicitors instructed Mr Richard Keightley of Hawkins to investigate the extent and cause of the flood risk to the Claimants’ property, on behalf of Warwickshire County Council’s insurer. The case was heard in a six day trial at the Technology and Construction division of the High Court in November 2019. Warwickshire County Council’s case was put by Mr Jonathan Mitchell of counsel, with evidence given by Expert Witnesses for all three parties.

The Claimants’ expert relied on a computer model of the watercourse, which had been developed previously to support the planning applications. The model suggested that the field was at risk of flooding from the watercourse overtopping its banks, and that enlarging the culverts would reduce the risk of flooding, while removing the culverts would remove that risk of flooding. The Claimants’ expert concluded that the model showed that the culverts were causing the watercourse to ‘back up’ and flood the Claimants’ property.

Mr Keightley found that the model was not accurately replicating the water levels in the watercourse and frequent flooding of the field, which were shown in the Claimants’ photographs. He explained that there were several reasons for this, including the methodology that had been used to model the catchment hydrology (which underestimated the flow in the watercourse when compared to other methods). Most crucially however, the parameters used in the model did not replicate the actual hydraulics of the culverts and watercourse.

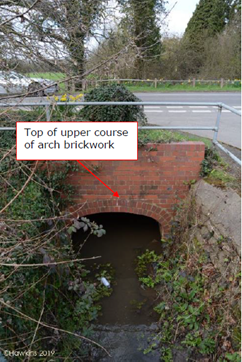

Warwickshire County Council’s culvert; a photograph taken during Mr Keightley’s survey (L) and a photograph taken by the claimants during a flood event (R).

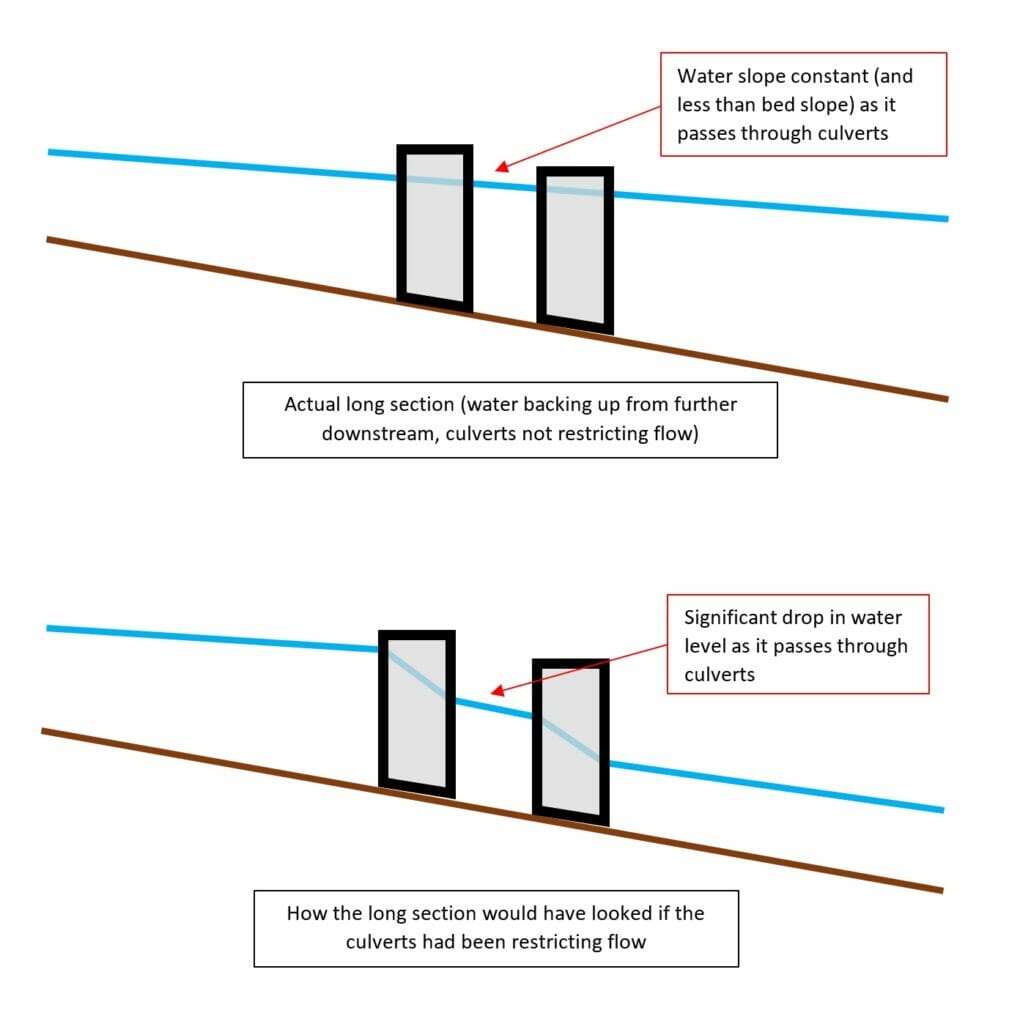

Mr Keightley used the Claimants’ photographs to demonstrate that the level of the watercourse downstream of the culverts during the flood events was higher than the model predicted. He also showed that the actual slope of the water as it passed through the culverts during the flood events was very shallow, and less than the slope of the base of the watercourse. Using ‘first principles’ hydraulics he explained to the Court that this showed there was a ‘hydraulic control’ downstream of the culverts, which was causing the watercourse to ‘back up’ and flood the claimants’ property. In other words, the culverts did have sufficient capacity and were not the cause of the flooding. If they had been, there would have been a significant drop in water level as the watercourse passed through the culverts.

Mr Keightley concluded that the culverts were not causing a risk of flooding to the Claimant’s property. He concluded that the risk of flooding arose primarily due to the field’s low-lying nature and limited permeability, and due to a hydraulic control in the watercourse downstream of the culverts (potentially overgrown vegetation and obstructions within the watercourse, or a smaller diameter culvert further downstream).

“I found Mr Keightley to be an impressive witness. Mr Keightley was rigorously cross-examined by Mr Darton and was criticised in his closing submissions for lack of independence. I disagree with that criticism. Mr Grime described Mr Keightley’s evidence as of ‘lecture quality’. Whilst Mr Keightley was not always ready simply to agree or disagree with questions put to him, my impression was that was because he was a careful expert witness using language with precision, who sometimes did not recognise the terminology used in the questions or who did not want to give an answer that he did not consider was strictly scientifically accurate”.

The claims against both local authorities were dismissed, with the Judge concluding that the cause of the flooding “was obstruction of the channel, not any inadequacy in the design or dimensions of the culverts. In particular, I accept the evidence of Mr Keightley that it is likely that any obstruction or hydraulic control to the flow of the water in the brook was downstream of both culverts”.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Richard Keightley is a Chartered Water and Environmental Manager and Chartered Environmentalist. He specialises in the investigation of flooding, water ingress and drainage issues, and has provided CPR-35 expert witness evidence in civil claims for both claimants and defendants. Richard joined Hawkins in 2017 as part of our civil engineering team, having previously worked at two major engineering consultancies, a water and sewerage company and New Zealand’s National Institute of Water and Atmospheric research