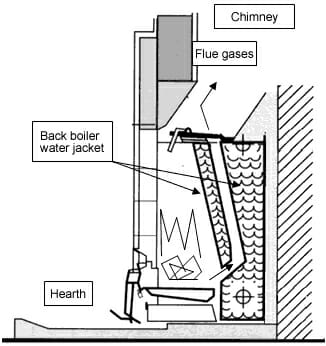

Back boilers are often located within a chimney breast behind either an open fire or range cooker, and they are typically installed during a house’s initial construction. Therefore, they are often forgotten about when a house is sold and purchased by a new owner. Back boilers operate by using the fire from the fireplace to heat water inside them. The hot water from the back boiler is then distributed to wall-mounted radiators to heat the rest of the house, and often to a hot-water storage cylinder to provide domestic hot water. Between 2003 and 2019, the percentage of homes in England that used back boilers as their main heat source fell from 12% to 1.4% according to a survey sample of 13,332 homes [1].If applied to the entire UK population, which consists of almost 28 million households (in 2019) [2], the number of homes with a working back boiler fell from approximately 2.9 million (in 2003) to 0.4 million (in 2019).

The figures demonstrate that between 2003 and 2019, the number of back boilers being used as the primary heat source within homes decreased by around 2.5 million. While this includes back boilers in houses that were demolished and replaced by ‘new-build’ homes, the figure also includes a proportion of back boilers that were made redundant when existing homes were converted to more modern, economical and environmentally responsible heating sources such as condensing gas boilers. Therefore, the figures suggest that there is likely to be a considerable number of redundant back boilers remaining in homes throughout the United Kingdom.

BLEVEs, or Boiling Liquid Expanding Vapour Explosions, involving back boilers occur when there is a small amount of water remaining inside a sealed back boiler following the decommissioning process. Water can also enter the back boiler if the plumbing installation is modified or when condensation accumulates on the internal surfaces within the back boiler. When the water within the back boiler is heated, most often from the lighting of a fire in the fireplace, it begins to increase in volume. The contents of the back boiler are normally directly connected to open-air by either uncapped open-ended pipework or by a hole in the boiler, and at atmospheric pressure, this would normally result in the gradual transition of the water into steam when the temperature of that water reaches 100°C (i.e. boiling).

However, if there is insufficient space for this expansion to occur (e.g. if the back boiler is sealed), the pressure in the system will increase (the volume of steam at atmospheric pressure is approximately 1600 times that of liquid water) and much of the water will remain as a superheated liquid. A superheated liquid occurs when a liquid’s temperature exceeds its boiling point at atmospheric pressure. The increasing pressure will exert a significant force on the boiler case and is often accompanied by noises that can be heard within the chimney breast. In some cases, the pressure also causes cracks to appear in the plasterboard around the fireplace.

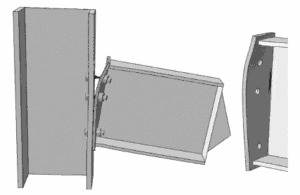

When the internal force exerted on the back boiler by the rising pressure exceeds the strength of the back boiler’s welded seams, the back boiler ruptures. The rupture creates a sudden pressure drop, by virtue of it creating a direct connection between the superheated water and the surrounding atmosphere, which allows the superheated water to ‘flash’ instantaneously into steam, thereby increasing its volume 1600-fold.This change in volume is the equivalent of the water in the tank shown in the image below expanding to fill the size of an Olympic swimming pool!

The almost instantaneous transition from water to steam generates a substantial pressure wave that can both cause sections of the chimney breast to explode outwards into the room, and shift the building’s walls, resulting in severe structural damage. The force of the explosion can also cause fires to develop when burning material within the fireplace, such as coal or wood, is projected outwards into the room.

In order to prevent BLEVEs from occurring, the Health and Safety Executive, along with other industry bodies such as the Heating Equipment Testing and Approval Scheme (HETAS), advise that a redundant back boiler should be removed from the home. Where this is not possible, the back boiler should have a hole drilled in one of its panels so that pressure cannot build up.

Despite these recommendations, Hawkins has investigated numerous incidents in both residential and commercial properties, where the back boiler has ruptured, causing considerable damage to the building and injury to its occupants. In these instances, the back boiler had been left in situ and in such a condition that a BLEVE was able to occur. In some instances, the back boiler was decommissioned, but left in a sealed condition; while in others, the pipework within the house was modified after the back boiler had been decommissioned, which caused it to become sealed. Environmental effects such as cold weather can also result in a redundant back boiler becoming sealed by ice, even if only for a limited time.

As part of our investigations, we consider the possibility that either inadequate decommissioning or defective subsequent modifications to the pipework, may have occurred previously. These can be forgotten or go unnoticed for many years until the fireplace is either reinstated or reused after the house has been purchased by new owners leading to a BLEVE.

Hence, when purchasing a new property, it is important to check whether or not a decommissioned back boiler was left in situ and, if it was, that any tradesperson working on the plumbing installation is made aware of the back boiler before they make any modifications to the pipework within the building. If a back-boiler is found, it must either be removed or have a hole drilled in its casing as per the HSE advice.

Hawkins can assist in the investigation of cases where a BLEVE is suspected. We are able to inspect the incident back boiler and adjoining pipework to confirm whether a BLEVE has occurred. Hawkins’ investigators can then discuss the relevant background circumstances with witnesses to determine what might have caused the BLEVE to occur.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr Tom Peat is a Chartered Engineer and a member of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers (IMechE). Tom graduated with an MEng in Aero‑Mechanical Engineering from the University of Strathclyde before returning to complete a PhD in Advanced Surface Engineering within the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering. Since joining Hawkins in 2017, Tom has investigated numerous commercial and domestic fires, escapes of water and oil, and other engineering related cases.