Germination failure for farmers can be expensive. It is not just the cost of the seed but the field preparations and operations before and after the crop failure that need to be taken into account should a failure occur.

Part 1: The Importance Of Seed Quality discussed the potential factors that can affect seed before it is sown. This part now covers seedbed preparation, sowing operations and environmental conditions.

Soil

Soil characteristics can affect the ability of the seed to germinate and subsequently emerge. Those affecting germination could be summarised as those which affect seed-to-soil contact or soil water status and therefore the rate and duration of seed imbibition; the uptake of water by the dry seed. Factors affecting emergence are largely those that influence impedance, which is sensitive to the moisture content of the soil, for example clod size distribution or sowing depth.

There is up to 90% establishment in sandy soils compared with 65% for loams and clays (Blake et al, 2003). The proportion of sandy soils in UK regions may affect cereal establishment. In winter crops on average between 1977 and 2002 there was 78% establishment rates in East Midlands and South East, 69% in the North East and Scotland and 60% in the South and South West.

Seed Bed Preparation

Previous crops have a significant effect on establishment. According to Blake et al, 2003, establishment after oats was 79%; potatoes, set-aside and peas was 66-72%; wheat, rape and beans was 54-60%.

Some previous crops harbour pests and diseases. Winter cereal crops after two-year-old ryegrass leys are considered to be vulnerable to frit fly. Cereal crops sown after sugar beet, potatoes and onions are vulnerable to wheat bulb fly attacks. Vegetable and salad crops such as peas, potatoes, carrots and lettuce grown before oilseed rape increase the risk of Sclerotinia disease.

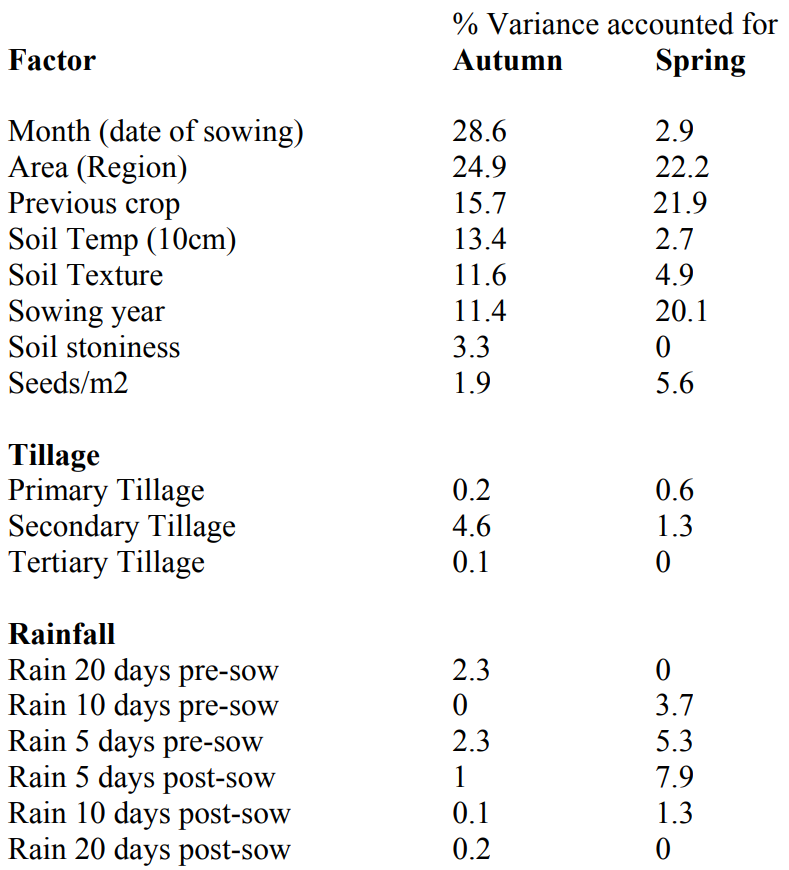

Cultivation method appears to have little effect on establishment, although there were insufficient types of cultivations within the research to allow strong conclusions to be drawn. However, tined cultivation appears to be the most successful.

Sowing

Variety: There is a significant effect of variety on establishment. Amongst seven varieties, for which there were sufficient data, establishment varied from 61% to 73% (Blake et al, 2003).

Depth: Shallow sowings are believed to make plants more vulnerable to frost damage, since the roots, which are the most frost sensitive part of the plant, are nearer the surface and more exposed to the ground frost. Hence, it is important that the drilling equipment is set to drill at the correct depth.

Density: The most appropriate target plant population depends on weed pressure and sowing date – the target should be about 150 plants/m² in the thinnest areas of the field and more if it is necessary to compete against weeds. Delayed sowing, which may be necessary for weed control or due to soil conditions, reduces the tillering period[1]. For each month drilling is delayed, an extra 50 plants/m² are typically needed to compensate for reduced tillering. Incorrectly calculating the sowing rate per hectare will lead to either running out of seed or having an excess left over.

Timing: Over-winter survival is important as spring plant population influences yield potential. Spring populations in some regions are about 15% lower than autumn populations. Sowing date has the greatest effect on establishment, with establishment decreasing from about 70% for September to early October sowings to 60% in late October, to less than 50% in November and later (Blake et al, 2003). The effect of sowing date appeared to be caused by lower soil temperatures, with establishment decreasing rapidly when the soil temperature at 10cm depth fell below 8°C.

Temperature: There are consistent effects of soil temperature. When sown at a depth of 10cm optimum soil temperatures are 8-12°C for earlier drillings and 12-16°C for later drillings. The different optimum temperatures according to sowing date are thought to be due to interactions with soil moisture.

Many growers do not keep records of exactly where individual seed batches were sown, the number of seeds sown, or the number of plants established, making it difficult to find an exact cause of germination failure. Batches of seed can be mixed or blended, either in the hopper of the seed drill or beforehand and sown in more than one location. This means that effects of seed batch on germination are not always obvious.

Post-Sowing Conditions

The effect of weather conditions is complex, with post-drilling rainfall improving establishment when the soil temperature is above 12°C, but decreasing establishment when it is below 12°C.

Waterlogging has been shown to prevent oxygen diffusion to respiring plant tissues. Although most emerging seeds and plants can survive short periods, if soils are waterlogged for an extended period plants will die.

Frost heave can occur where soil surface structure is such that when ground frosts occur the soil particles freeze together and expand damaging the shoots of protruding seedlings. This is most common on light structureless soils, or where more full-bodied soils are over-cultivated leaving an excess of fine surface tilth.

Our third and final part of this series of articles covers the pests and diseases that can affect crop germination.

[1] Tillering begins around 40 days after planting and can last up to 120 days.

About the Author

James has over 20 years’ experience in his field, and is experienced in investigating the causes of plant diseases, crop failures and spoilage of fresh produce.

He has worked on projects to breed genetic resistance to diseases in oilseed crops and published research into the effects of climate change on plant diseases in the UK. James has also managed a portfolio of field and glasshouse research projects, gaining extensive experience in plant disease diagnostic techniques.

James joined Hawkins as a Senior Associate based in our Reigate office after four years at Berry Gardens Growers, the UK’s leading berry and stone fruit cooperative. During his tenure, he set up the plant disease diagnostic laboratory, and used his expertise to diagnose crop problems and fruit rots and advise growers on disease management strategies.

James has investigated cases of crop germination failure, crop storage problems, fallen trees, mould contamination, pesticide damage, wildfires and plant disease outbreaks in domestic and commercial settings.