When we consider the concept of an explosion, our initial thoughts often gravitate towards the more apparent and commonly encountered scenarios like the fireballs of movie special effects, the boom and incandescent lights of fireworks, or the images of a building collapse due to a gas explosion. However, whilst these might be commonly thought of scenarios, explosions can cover a surprisingly broader range of incidents of forensic concern.

Explosions can occur intentionally (such as military operations, quarrying/mining and special effects), and unintentionally, due to the ignition of escaped natural gas or the rupture of a pressure vessel.

So, What Exactly is an Explosion?

An explosion is an event where there is a rapid outward release of a large amount of energy, usually in the form of heat, light or sound, accompanied by a pressure wave or a shockwave.

Typically, explosions are classified under three types:

- Chemical

- Physical

- Atomic (nuclear)

This article focuses on chemical and physical explosions and explains the conditions in which they can occur.

Chemical Explosions

A chemical explosion occurs when a chemical substance or mixture undergoes decomposition or a change of state, rapidly releasing a significant amount of heat and gas, typically within one-hundredth of a second (to put 0.01 seconds into perspective, this is approximately 10 times faster than the blink of an eye).

Explosives, used for both military and civil applications (e.g. mining and demolition), are the most recognisable cause of a chemical explosion and are categorised as either “low” or “high” explosives.

Low explosives are classified as having a burn rate of less than 1000 meters per second. This is exemplified when the black powder known from antiquity, undergoes deflagration – a rapid burning process. Deflagration occurs at the surface level of the material and the burn rate is influenced by particle size; the finer powders react (burn) more quickly than coarser ones.

When ignited in the open, a low explosive will generate light and sound, but it won’t undergo a full explosion unless it is confined. Confinement enhances the reaction rate by retaining heat, leading to increased rates of gas production and pressure build-up until the confinement ruptures, resulting in an explosion. Confinement of low explosives can also be harnessed to direct the flow of the gas produced, such as in a rocket motor or firework.

A low explosive normally comprises a fuel, an oxidiser and a sensitiser. The sensitising component is present to lower the temperature required to ignite the composition, resulting in an increased rate of reaction between the fuel and oxidiser . For instance, in the black powder, sulphur acts as the sensitiser as it melts at a lower temperature than carbon and also serves as a fuel in the reaction. Low explosives (depending on the precise composition) can be ignited by friction, heat or shock (i.e. impact).

High explosives (e.g. dynamite) detonate when a shockwave causes decomposition of the compound as it travels through it. The shockwave travels through the material at a velocity faster than the speed of sound in air, i.e. faster than 1000 metres per second. For some explosives, the velocity of detonation is approaching 8000 metres per second. The result is effectively an instantaneous decomposition of the entire bulk of explosive material, generating a large volume of gases.

Owing in part, to the speed of the decomposition a high explosive does not need confinement to explode, because the bulk compound itself forms the confinement for the explosion. When a high explosive detonates, as well as producing light, heat and sound, the energy is experienced as pressure (pushing) and shattering (brisance).

High explosives are further divided into two categories (primary and secondary) depending on how sensitive the explosive is to ignition. Primary explosives are very easily initiated by friction, heat or shock. Primary explosives are very hazardous to handle and are only practical for use in detonators. A detonator is a device that can be invited (e.g. by an electric current or shock) to produce a shockwave to initiate the detonation of a secondary explosive.

The detonation of a secondary explosive is not easily initiated by friction, heat or shock, but they have high velocities of detonation and energy compared to primary explosives. This means a secondary explosive is generally safer to handle, but can produce more energy, than a primary explosive.

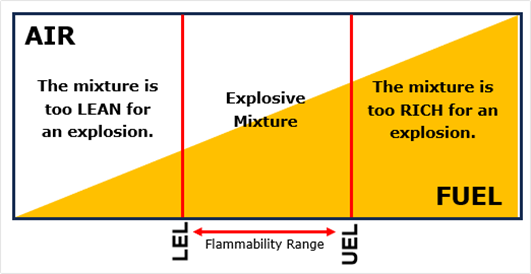

Aside from explosive materials, a chemical explosion can also occur if a mixture of flammable gas or vapour with air (i.e. oxygen), or another oxidiser (e.g. chlorine), is ignited. However, for a gas/vapour and air mixture to be ignited and potentially explode, the percentage concentration of the components of the mixture in air (oxidiser) must be within a specific range for that gas or vapour, which are defined as the lower explosive limit (LEL) and the upper explosive limit (UEL)[1].

The LEL and UEL are critical parameters that define the flammable range of a gas-air or vapour-air mixture.

The LEL is the minimum concentration of a flammable gas or vapour in air below which the mixture is too lean to ignite. If the gas or vapour concentration is below the LEL there is insufficient fuel for combustion, and thus an explosion can occur.

Conversely, the UEL is the maximum concentration of a flammable gas or vapour in air above which the mixture is too rich to ignite. If the gas or vapour concentration exceeds the UEL, there is insufficient oxygen for combustion, and thus an explosion occurs.

The concentrations between the LEL and UEL is known as the flammability range, i.e. the concentration of the gas or vapour that can be ignited and/or explode (Figure 1).

For methane (i.e. mains gas) the range limits are a LEL of 5% (by volume) and a UEL of 15% (by volume)[2].

Ignition of a flammable gas or vapour in air mixture (within the LEL and UEL range) results in the rapid production of a large volume of combustion products, mainly hot gases (e.g. carbon dioxide and steam in the case of methane and air) and, the expansion of those hot gases produces a pressure/shock wave. Possible sources of ignition are similar to explosives, e.g. electrostatic discharge/electric arc, friction, a hot surface or an open flame.

The ignition source must provide a minimum ignition energy (MIE), or ignition will not occur, particularly where the ignition source is an electrostatic discharge or electric arc. In general, as the concentration of a flammable gas or vapour in air approaches the extremities of the flammability range (near the LEL and UEL) the MIE increases, as lean or rich mixtures require a higher energy ignition source.

Another frequently encountered example of a chemical explosion is caused by the ignition of a high concentration of finely divided power (dust), e.g. coal dust, custard powder, flour or powdered metals , in the air or another oxidizing chemical. This situation is similar to a flammable gas-air mixture. Therefore, as with gas/vapour air mixtures, the concentration of the dust/air mixture must be within flammability limits to be ignited.

There are five conditions required for a dust explosion, as represented by the dust explosion pentagon (Figure 2).

For example, in agricultural dusts (< 74 μm particles) the LFL is in the range between 20 and 200 g/m³ and in plastic dusts, the range is between 20 and > 2000 g/m³[3]. For dusts, the UEL is of less significance, as mitigation against a dust explosion occurring would be to always prevent the concentration from exceeding the LFL. Furthermore, for a normally occupied space, dusts will present a hazard to health, e.g. respiratory conditions, well below the LEL concentration.

When dust is dispersed in the air, in conjunction with its large surface area, ignition of the flame front spreads rapidly throughout the dispersed dust. The resulting rapid burning (another example of deflagration) causes the rapid production of combustion products (gases) and a pressure wave. The heat that can be produced by the resulting explosion is related to calorific value of the dust, as this will limit the speed that the oxidant is consumed. However, a dust explosion under the right conditions can also detonate creating a shockwave.

A consequence of a dust explosion can be an even larger secondary explosion when the pressure wave from the primary explosion lifts and disperses more dust into the air, which is then instantly ignited by the heat from the primary explosion.

Physical Explosions

A physical explosion is caused by the sudden release of mechanical energy. Typically, a physical explosion occurs due to the release of energy from a confined space resulting in the rapid expansion of gases or other materials. Depending on the specific conditions, a physical explosion can create a shockwave.

A physical explosion occurs when the pressure inside a sealed vessel exceeds the vessel’s tensile strength resulting in its catastrophic failure, such as rupture and possibly fragmentation of the vessel.

An example of a physical explosion is a boiling liquid expanding vapour explosion (BLEVE). This occurs when a vessel containing a compressed substance (e.g. liquified petroleum gas (LPG) or water) undergoes a rapid phase transition, e.g. water to steam. This is because whilst held under pressure as a liquid, the substance has excess heat needed to change its phase and thus once the pressure contrast is removed, the phase change happens virtually instantly.

If a vessel containing even a small amount of water is heated, the resulting expansion of the water to steam increases the volume by approximately 1600 times, resulting in the failure of the vessel. Such explosions can result in damage to structures comparable to that caused by a flammable gas or vapour explosion.

If a vessel containing a flammable substance (e.g. LPG) is externally heated, possibly by an already established fire, the resulting failure of the vessel will produce a physical explosion. However, the flammable and dispersed contents can also, if ignited deflagrate or detonate.

A high-energy electric arc flash is also an example of a physical explosion. The arc flash generates light (including in the ultraviolet (UV) wavelengths) and heat, resulting in the rapid heating of the surrounding air producing a pressure wave. The pressure wave can be sufficient to knock a person off their feet, notwithstanding that they are very likely to suffer flash burns due to the heat and UV light.

Nuclear (Atomic)

The energy released by uncontrolled nuclear fusion or fission is millions to billions of times more than that produced by either a physical or chemical explosion.

The Effects of Explosions

Regardless of the type of explosion, the effects are the same due to the release of energy as thermal heat, light, sound as well as a pressure wave/shockwave.

An explosion is very likely to result in structural damage, including the partial or complete collapse of buildings. If the explosion causes a shockwave, significant damage and injuries can occur well beyond the immediate vicinity of the explosion. This can be seen in videos posted of the 2020 Beirut harbour explosion, which was caused by a fire involving stored fireworks and ammonium nitrate fertiliser.

Explosions present a significant hazard of serious harm to people. This can result directly from the explosion or indirectly due to crushing or entrapment in a collapsed (partial or complete) structure and impalement by projectiles ejected by the explosion.

The heat released from an explosion is very likely to singe or scorch lighter materials, especially fabrics. A lean mixture of flammable gas/vapour and air is less likely to cause a fire than a rich mixture. An explosion may or may not result in a sustained fire. However, this does not discount the possibility that the explosion causes damage to something else, which then results in a secondary fire, e.g. the collapse of a structure damages gas pipework, where the escaping gas is then ignited.

Although linked to the pressure wave/shock wave, the sound produced can cause hearing loss, either temporary (possibly leading to disorientation), or permanent.

Investigating Explosions

Hawkins has extensive experience in investigating explosions.

It is often evident from the pattern of damage to structures and the presence of projected debris that an explosion has occurred. However, this will almost certainly be supported by witness evidence, who will report having heard a loud “bang”.

An initial step when investigating an explosion is to determine, if possible, whether or not another event, most likely a fire, preceded and caused the explosion. This can be hampered by the resulting damage from the explosion as this could mask any evidence of a precursor event. Similarly, a post-explosion fire could mask evidence as to the order of the events.

Once it has been established that an explosion has occurred, the primary step is to examine the evidence carefully to identify the source and cause of the explosion. On occasion, it might be necessary to consider undertaking the controlled demolition and clearance of a scene to provide safe access to examine and recover any items of interest.

Where a mains gas supply is suspected as the cause of the explosion, it will probably be necessary to identify and test (pressurise) the integrity of the gas carcass pipework to identify if there is evidence of any leaks. Ideally, this is completed before recovering the pipework for a more detailed laboratory examination. It is necessary to establish that any leaks found were present prior to the explosion and are not a consequence of the explosion.

In some circumstances, it can be beneficial to adopt a multidisciplinary approach for explosion investigations. An example of this is:

- A fire/explosion investigator is most likely to be the first responder at the scene to initially record and collect the witness statements and the physical evidence.

- Metallurgists and materials scientists can investigate certain possible causes of the failure in greater detail, for example. joint failures, corrosion of pipework, or damage to pipework or other components, the failure of which possibly caused the escape of a combustible gas or fluid.

- A civil/structural engineer can consider the impact of the explosion on the incident and surrounding structures, both with respect of safe access to the scene and to assist in determining if structures have behaved unexpectedly.

- There are also broader possible aspects such as assessing the contamination that can occur after an explosion and aspects including health and safety legislation, pressure vessel safety and the actions of various possible involved parties.

About the Author

Dr Richard J Fletcher has carried out over 1000 investigations during his tenure at Hawkins. He specialises in fires and explosions as well as personal injuries related to fireworks/pyrotechnics. His experience ranges from small domestic incidents to multi-million pound losses at commercial and industrial premises.

He is a member of the Association of Stage Pyrotechnicians and outside of Hawkins he has gained experience working for a firework display company and using theatrical pyrotechnics for theatrical performances.

Hawkins has a well-established multi-disciplinary team of investigators who will work to identify the type of explosion that has occurred, drawing in suitable colleagues’ expertise and resources as they seek to determine the cause. If you would like Richard, or a Hawkins expert from any other discipline to investigate an incident for you, get in touch.

References

1: LEL and UEL are interchangeable with the lower flammability limit (LFL) and upper flammability limit (UFL) of a substance.

2: Babrauskas V (2003) LFL and UFL for pure chemical substances (Table 1B, p 1043). Ignition Handbook, Fire Science Publishers.

3: Babrauskas V (2003) LFL for agricultural and plastic dust (Tables 9 and 10, p 1064). Ignition Handbook, Fire Science Publishers