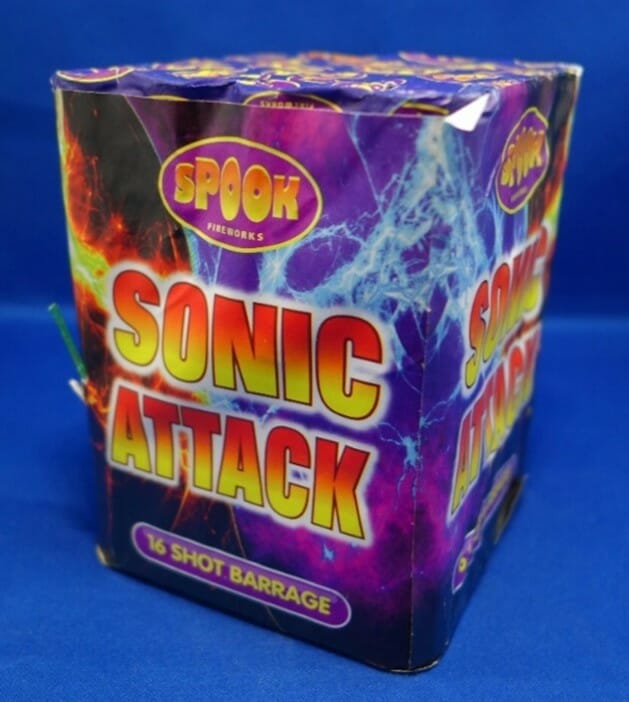

We are all probably very familiar with fireworks, especially the type commonly used in gardens on Bonfire Night, or those seen when watching professional displays at weddings and other celebrations. These types of fireworks are classified F1 to F4 in “The Pyrotechnic Articles (Safety) Regulations 2015,” covering all the types of fireworks from hand-held sparklers to the largest display shells used by professionals.

However, within the same legislation there are a further four classes of pyrotechnics: articles T1, T2, P1 and P2.

This article considers the significant differences between these four classifications of pyrotechnics, when compared to traditional fireworks, as well as their types, uses, and potential risks.

Theatrical Pyrotechnic Articles

The T1 and T2 classification “Theatrical Pyrotechnic Articles” (which can often also be referred to as Stage Pyrotechnics, Proximity Effects or Special Effects) covers pyrotechnic articles for use on stages and theatres; including use for television shows, movies, concerts and sporting events.

The majority of T1 classified pyrotechnic articles produce effects suitable for indoor use. The T2 classification, however, covers devices that produce generally larger effects, and therefore are only suitable for use in large arenas, stadia or outside venues. All require specific knowledge to ensure they are used safely.

There are a wide range of pyrotechnic effects available, including maroons and concussions, both of which produce reports (i.e. a loud bang), as well as devices that produce coloured flashes of light, puffs of smoke, jets of flames or eject sparks, coloured stars, confetti or streamers.

The majority of effects produced from T1 and T2 pyrotechnic articles occur instantly on ignition, and they are manufactured to produce consistent results (for example the height, duration and spread of the effect).This consistency in the effects produced is essential to ensure their safe use, specifically, because it likely that these pyrotechnic devices will be used on stages “close” to people. This is compared to the safety distances (usually in metres) required for F2 to F4 fireworks. This “closeness” of operation leads to the description of “proximity effect”, which poses a significant hazard to moving actors, musicians or dancers. Therefore, it is essential to carefully consider the type and size of the pyrotechnic effects that are intended to be used, to ensure the risk is minimised.

For the majority of T1 and T2 pyrotechnic articles, the intention is that they can be operated, or “fired,” immediately on a “cue,” examples of which include: the moment an actor says a line, as the band starts to play, or when a motorbike makes a jump. To ensure this is possible, these pyrotechnic devices cannot use the type of fuse commonly found on fireworks, which is lit with a naked flame and often has a delay before the effect is produced. Instead, T1 and T2 pyrotechnic devices are ignited by an electric match, which is a pyrotechnic device in itself, that is ignited when an electric current is passed through it. The ignition and effect are instantaneous, and the effects produced occur with no delay. In most cases the electric match igniter is integrated into T1 and T2 device at manufacturing. The coiled wire of the electric match can be seen in the photograph of the T1 Theatrical Flash.

To operate a T1 or T2 pyrotechnic article requires the use of a firing system to provide the necessary electrical current on cue. Firing systems can be either wired or wirelessly controlled and are designed with multiple safety circuits to minimise the risk of accidental operation.

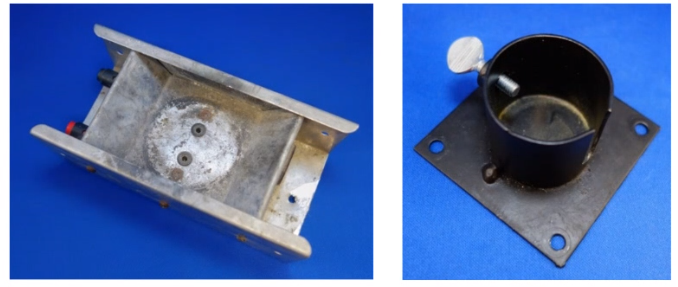

As T1, and in some cases T2, effects are likely to be used in “close” proximity to people, and often inside buildings or stadia, it is essential they cannot be accidentally or unintentionally moved or fall over. This could result in the effect being accidentally directed towards people or combustible materials (e.g. scenery).Therefore, in most cases the manufacturers also sell proprietary holders and supports for their pyrotechnics articles. Some types of holders incorporate electrical terminals for connection to the firing system and terminals on the pyrotechnic device. Theatrical maroons require the use of a fragmentation tank, to contain the spread of the device’s ruptured casing (which can be made from either carboard or plastic).

As Pyrotechnic articles all produce a combination of sound, light, smoke and heat, they pose direct risks of fire, personal injury and, potentially, death. The professional use of these pyrotechnics, e.g., theatre, film or television productions, falls within such legislation as the Health and Safety at Work Act and the Dangerous Substances and Explosive Atmospheres Regulations. It is essential that an operator considers the risks and possible mitigations before committing to use pyrotechnics at any venue. The demonstration of such consideration would almost certainly be by a written risk assessment.

A risk assessment would include the competence of the operator, overall risk, safe zones required for a particular effect, and sufficient time to assemble and load the effects. The risk assessment process would determine if the effects desired by the production are suitable for the venue, such as sound pressure levels produced by an effect. In addition, it would also consider what happens in an emergency (firefighting arrangements), including the fire safety procedures and arrangements of the venue itself (e.g. whether the venue has sufficient fire exits and if they are being kept clear).Communication is vital so that all those involved in the production are aware of both the effect and the safety zones, as well as to ensure that these can be monitored during both rehearsals and performance. Ideally, the operator would have direct line of sight to the pyrotechnics, allowing complete situational awareness prior to firing the effect or sequence of effects. If line of sight is not possible, then it would be necessary to have dedicated people to observe the area and have direct communication to the operator. Without exception, the person operating the firing system (and any observers) should have authority to decide whether it is possible to safely fire the effect, regardless of how that might affect the performance or show.

It is less likely that a “consumer” using such pyrotechnics would fully consider or complete such a risk assessment. This is in part the reasoning for a separation between T1 and T2 products, as in general T1 products produce smaller, more confined effects and pose less of a risk compared to T2 products if mishandled. As the majority of T1 devices available to the public require an electronic firing system, this means the consumer wanting to use them is faced with an extra cost involved in either hiring or buying a suitable firing system. This does lead to some being tempted to make their own electrical firing systems. However, such “Home Brewed” systems are unlikely to include suitable safety circuits, posing a significant risk of unintended or premature firing of an effect.

Other Pyrotechnic Articles

P1 and P2 are labelled “Other Pyrotechnic Articles”, which include devices such as, marine distress flares, bird scarers, and vehicle pyrotechnics (i.e. air bags and seatbelt pretensioners).Smoke generators and thunder flashes are also now widely used in military simulation games, e.g. paintball and airsoft. Most P1 and P2 devices are only suitable for use outdoors.P1 and P2 devices are likely to be ignited by various mechanisms, including safety fuses, electric match or a friction striker (match head type or a wire “ring” pull).

The only legal restriction in the UK for the sale of T1 and P1 pyrotechnic articles to a consumer is that they have to be over 18. However, it is likely that manufacturers and retailers will use their discretion as to whether or not they are willing to sell to a specific consumer.T2 and P2 can only be sold to “Persons with Specialist Knowledge”, but there is no formally recognised training or “licence” in the UK that proves someone has specialist knowledge. Although such a person is likely to be someone who has had training and/or experience, the responsibility to ensure a buyer has “Specialist Knowledge” rests with the supplier/retailer.

There are an increasing number of non-pyrotechnic effects also coming to the market, including machines that can produce sparks or flames, generate smoke, or eject confetti and streamers using compressed air. Whilst these remove the pyrotechnic component, they are not risk free. The sparks and flames produced still pose a fire hazard, and projectiles pose a risk of injury to people. As such, the use of these items should be carefully considered.

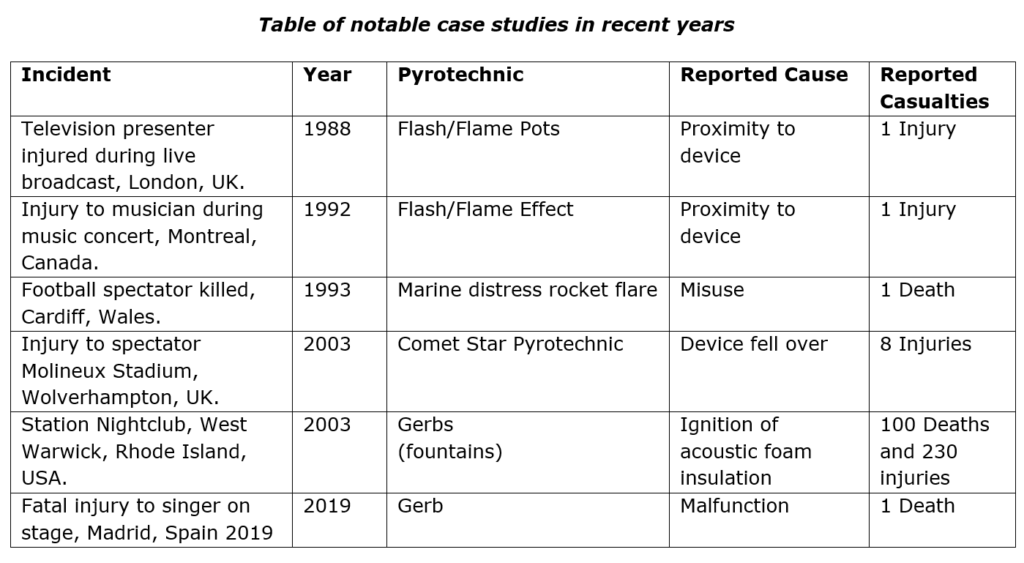

Incidents involving pyrotechnics, specifically T1 and T2 type theatrical pyrotechnics have resulted in both injuries and fatalities.

One of the earliest records of a fire resulting from the use of “Theatrical Pyrotechnics” effect occurred in 1613 (pre-dating the current legislation by some 400 years).This was during a performance of a Shakespeare play (possibly Henry VIII) at the Globe Theatre, in London. The contemporaneous reports indicate that some “stage cannons” were fired to mark the entrance of the King. A piece of burning wadding ejected from one of the cannons landed on the thatched roof of the building. The whole building burnt to the ground within an hour. The reports of the incident indicate someone’s clothes were set on fire and had to be extinguished with a bottle of ale but there are no known fatalities.

In modern times incidents have also occurred during music concerts, television productions and at sporting events. Some of the most significant incidents worldwide, when considering fatalities, have occurred in nightclubs.

There have been at least ten fires in nightclubs worldwide since 2000 attributed to pyrotechnics. These incidents have resulted in the reported deaths of over 800 people and many more injured. Two of these incidents occurred in Brazil, the first was in 2001 and the second in 2013. A summary of six of the more recent incidents associated with the use of pyrotechnics are provided below:

The surprise and implicit magic from the sound, light and colour from pyrotechnics creates a unique physical effect on an audience’s or spectators’ senses that is hard to fully replicate using non-pyrotechnic methods. However, it is clear that in using pyrotechnics there are associated risks of starting a fire, injury or even death. The pyrotechnician has a significant duty to fully consider the risks prior to the use of pyrotechnics, and, when suitable, to also put the necessary controls to mitigate those risks in place. If no risk assessment is conducted, or the identified risks cannot be mitigated, then pyrotechnics should not be used.

About The Author

Richard J Fletcher holds a degree and PhD Chemistry. He is involved in investigating fires and explosions as well as personal injuries related to fireworks/pyrotechnics. He is a member of the Association of Stage Pyrotechnicians and outside of Hawkins he has gained experience working for a firework display company and using theatrical pyrotechnics for theatrical performances.

Italiano

Italiano