The HSE publishes data each year on fatal and non-fatal injuries to workers that occur in the previous period. Regrettably, some of these injuries occur because of unsafe lifting operations. Lifting operations are not limited to large cranes on construction sites, but can occur in a range of industries and activities, for example:

- The manufacturing industry uses overhead gantry cranes and hoists.

- Delivery firms and storage facilities use forklift trucks and telehandlers to move items.

- Excavators used for lifting in construction works, waste recycling companies and other industries.

- Scissor lifts and cherry pickers can be used in many situations to provide access.

Compliance with UK legislation regarding occupational health and safety forms a hierarchy, at the top of which is the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974. This requires that employers protect the health, safety and welfare of their employees at work. Under this Statute numerous Regulations exist, for example the Construction (Design and Management) Regulations 2015 and the Workplace (Health, Safety and Welfare) Regulations 1992. Another key regulation is the Lifting Operations and Lifting Equipment Regulations 1998 (LOLER) which governs lifting operations and the equipment used. The main part of LOLER is Regulation 8, “Organising of lifting operations”.

To assist in compliance with these Regulations, the HSE produces Approved Codes of Practice (ACOPs) which are third in the compliance hierarchy. To assist further with the understanding of legal duties and how to adhere to them, the HSE produces numerous guidance documents (fourth in the hierarchy), most of which are available from the HSE website. Other guidance documents and codes of practice (often written in conjunction with the HSE) are also available through National Industry bodies and such publications form the fifth and final level of the compliance hierarchy.

PLANNING LIFTING OPERATIONS

There are three main requirements set out by LOLER when organising lifting operations:

“Every employer shall ensure that every lifting operation involving lifting equipment is –

a) Properly planned by a competent person;

b) Appropriately supervised; and

c) Carried out in a safe manner.

Under UK legislation, all work activities must be risk assessed and have a safe system of work. One of the most important parts to a lifting operation is the lifting plan, which is essentially the risk assessment and system of work for lifting operations. This plan must be carried out by someone competent and in good time before the lifting operation commences. For lifting involving cranes, this competent person is known as the ‘Appointed Person’ or ‘AP’. For more involved operations, the plan can often be split into an initial overview and then more detailed sections covering each stage of the operation.

The initial overview will outline what is generally going to happen, what equipment is to be used and how the risks are to be controlled. This initial plan should also identify the complexity of the lifting operation and whether it can be classed as “routine” or “non-routine”. According to the HSE LOLER ACOP, routine lifting operations can be covered by a standard plan with a generic risk assessment.

The individual routine lifting operations can then be planned by the people using the lifting equipment such as the operator, providing they have suitable knowledge and experience to do so. In contrast, non-routine lifting operations should planned each time the task is carried out.

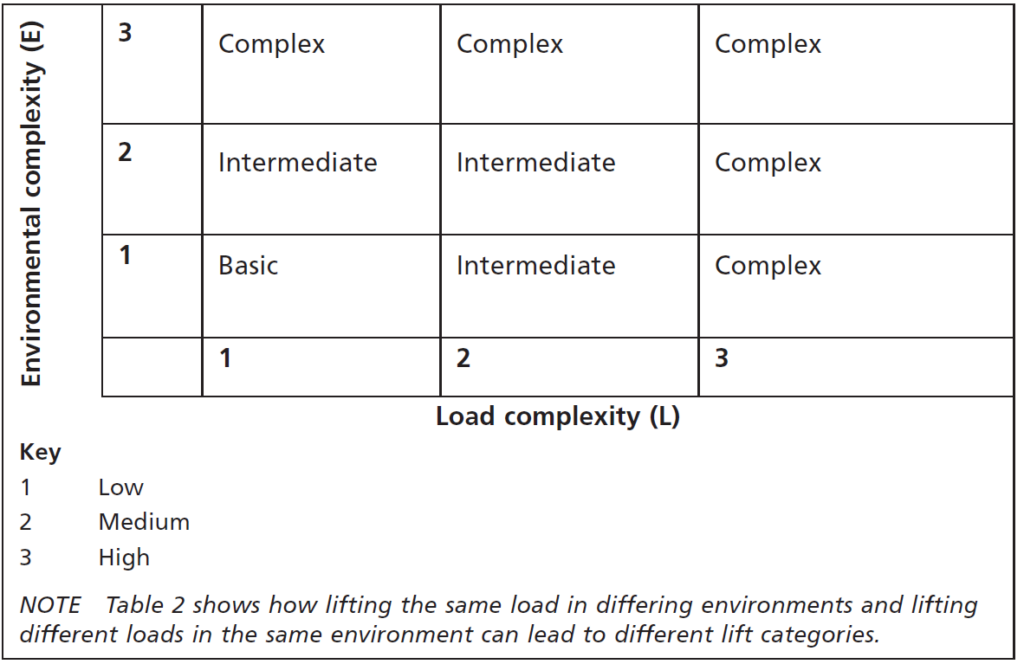

The complexity of the lifting operation needs to be considered so that proportionate levels of controls are applied to mitigate the risks. The complexity will be a function of the hazards associated with both the environment and the load. A suite of standards, BS 7121, exist in the UK to provide guidance in carrying out lifting operations using cranes. Below is a table from the first of this series which gives an example of the classification of the complexity of lifting operations.

Examples of environmental hazards include: rain, wind, overhead power lines, poor ground conditions and adjacent activities. Load hazards include: uncertainty of the weight or centre of gravity of the load, a fluid load (e.g. containers filled with water) and the integrity of the load.

KEY PARTS TO THE LIFTING OPERATION

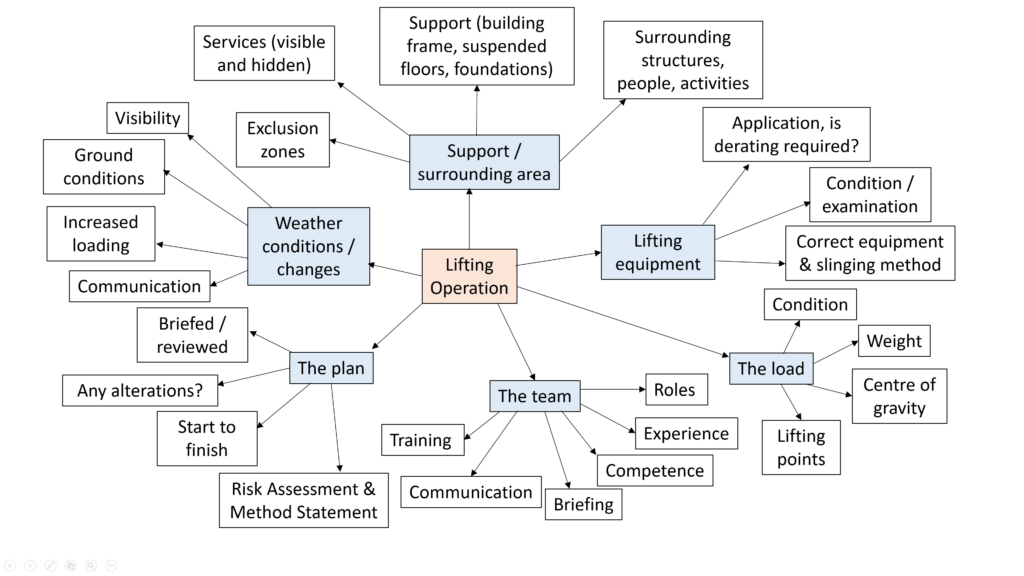

When planning the lifting operation, relevant guidance documents should be reviewed to ensure all aspects of the operation are conducted in a safe and controlled way. Below are some examples of aspects that should be considered:

EXAMPLES OF FAILINGS IN LARGER SCALE LIFTING OPERATIONS

In our experience, if the lift plan is developed by a competent person, reviewed and the lifting team are briefed, most problems can be identified before the lifting starts. Nevertheless, complications can arise before the operation begins or during the lifting operation due to unplanned or unforeseen hazards. We have provided a few examples below, but by no means is this an exhaustive list:

- Variations in the environment: a weather forecast is exactly what it claims to be, a prediction. As lifting operations begin or continue, the wind speed can become higher than planned or gust leading to increased forces or unstable suspended loads. Rain can also increase the weight of the load and affect the ground conditions and visibility. If the weather changes during the lifting operation, the risks need to be reassessed by a competent person.

- Excavators: in some instances, an employer may decide to use excavators for lifting operations but must be aware of the high risks involved. For example, the excavator driver could accidentally catch the controls with their coat leading to unintentional, fast movement of the excavator and load. In the past this has caused injury to nearby workers coming into contact with the load. The prevent this, the safety lever inside the excavator should be raised to isolate the controls of the machine when workers are in the danger zone.

- Assumptions of the load: sometimes the load weight or centre of mass is either approximated or cannot be accurately determined. This can lead to overloading the lifting equipment or unstable suspended loads. In these situations it is important to consider a detailed assessment by someone qualified or to introduce safety factors/measures to mitigate the risk.

- Lifting equipment failure: sometimes failures of lifting equipment can occur if the equipment is damaged, overloaded or the wrong equipment (which does not have the capacity to carry out the lift) used. To avoid this, the lifting plan should always specify what equipment should be used and the equipment should be checked for damage prior to use. If the planned equipment is damaged or missing, alternative equipment should not be used without the approval of the competent person who planned the lift (even if it is thought to be “better”).

- Support: sometimes the pressure applied by the crane or the capacity of the support beneath it is underestimated and can lead to overturning or failure. The presence of buried services can also be overlooked.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Richard Giles-Carlsson has extensive experience in Civil Engineering, having worked on large projects such as the Bond Street Station Upgrade in London and the Davyhulme Wastewater Treatment project in Manchester before joining Hawkin’s Civil & Structural Engineering team in 2017. Richard is an Incorporated Engineer and a Member of the Institution of Civil Engineers