Types of Scaffold

Scaffolds are temporary structures that are assembled from components and often used to either provide a temporary working platform, or temporary access to a place of work. The term ‘scaffold’ is an umbrella term that incorporates a wide variety of different types of systems. Although nowhere near as popular in the rest of Europe, the most common type in the UK is ‘tube and fitting’ scaffold, which comprises hollow, plain ended, steel tubes that are connected together using couplers. Alternatively, proprietary scaffold systems are available, for example ‘cuplock’ or ‘kwikstage’ scaffolds, which substitute couplers for integrated connections.

The layout of the scaffold will depend on its purpose, but one of the benefits of using scaffolding systems is their versatility. Standard scaffold layouts can include ‘tied towers’ or ‘birdcages’, whereas more complex arrangements can bridge over other structures or features, or include other complexities such as relatively high loads or complex connections. In one instance, Hawkins investigated water ingress through the roof of an existing structure where a scaffold temporary platform had been been erected above it. This scaffold system was supported by a network of scaffold beams, and vertical scaffold tubes which pentrated through the existing roof. This scaffold also provided support to construction work above, and such a scaffold often requires a bespoke design.

Scaffold Layout and Design

- What is the aim of the scaffold; is it a working platform, or does it simply provide access?

- How long will it be needed for?

- How many people or companies are likely to need to use it, and how often?

- How will materials and equipment be transported up to height; is lifting equipment available or will operatives need to carry items?

- Have emergency procedures been considered?

- Will it need to be altered at any point to allow for changes in site conditions, or the requirements.

Like all structures, scaffolding needs to be ‘designed’ by someone competent. In most cases, scaffold ‘design’ will fall under one of two categories. Either the scaffold comprises a ‘standard’ arrangement, or it is considered ‘non-standard’ (or complex). Standard scaffolds do not typically require a formal bespoke design, and instead they can be erected in accordance with the recognised UK guidance, TG20:21 (or formally TG20:13) issued by the National Access and Scaffolding Confederation (NASC). Alternatively, non-standard scaffolds will require a bespoke design, and this design will normally need to be completed either by a structural engineer, or by an advanced scaffolder (perhaps with some input from a structural engineer). There are also specialist scaffold designers. Formal designs typically include drawings (or plans) to assist with understanding the arrangement of the scaffold to be erected, and often highlight any specific requirements or hazards.

Assembling Scaffolds and Training

The Work at Height Regulations 2005 (WAH) requires that scaffolding is only assembled, disassembled and significantly altered by persons who are competent to do so, or persons who are supervised by someone competent. Competency in scaffolding is most commonly evidenced by operatives attending training courses accredited by the Construction Industry Scaffolding Record Scheme (CISRS). The three levels of formal qualification are:

- Part 1 - trainee scaffolder

- Part 2 - scaffolder

- Advanced Scaffolding - advanced scaffolder

Training is typically valid for five years, at which point refresher training can be undertaken to renew the qualification. The completion of such training often results in the issuing of a competency card, and it is standard practice for operatives (both scaffolder and other operatives) to have their competency cards ‘to hand’ in case they need to prove their competency on site.

Work at height, including the erection of scaffolding, is a hazardous activity, and regrettably, injuries occur during scaffolding work. To provide guidance in preventing this, the NASC issued a pocket booklet, with the current (as of 2022) version being titled ‘SG4:22 Preventing Falls in Scaffolding Operations’. This provides an overview of how to erect scaffolding safety, and includes the following topics:

- The scaffolder’s ‘safe zone’

- Fall protection measures, including personal protective equipment and types of lanyards

- Anchor points for lanyards

- Advanced guardrail systems

Handover and Inspections

WAH requires that scaffolds are inspected before they are first used. This initial inspection is commonly completed by the scaffolding firm that erected the scaffold, although, strictly speaking, it just needs to be completed by someone considered competent. It is also common practice for this initial inspection to be followed by a ‘handover certificate’. This certificate is completed by the person inspecting the scaffold and should advise that, at the time of inspection and handover, the scaffold had been erected to the client’s specification and in accordance with either a bespoke design or guidance included in TG20:21. A handover certificate will often also remind the user of the scaffold about their obligations to ensure it is inspected and checked.

WAH also requires an inspection of scaffolding after significant changes are made, or in the event of something that might jeopardise the safety of it, such as adverse weather conditions. If neither of these are a factor, then scaffolds should be checked daily or, each day works are undertaken on the scaffold, and then formally inspected at least every seven days. Daily checks look for obvious issues and can be completed by non-scaffolders, whereas routine formal inspections need to be completed by someone competent in scaffolding (i.e. a scaffolder or someone with specific training in scaffold inspections).

Examples of Incidents Involving Scaffolding

The term ‘storm’ is often used in insurance claims when referring to relatively serious weather conditions. However, this term can sometimes be used to try and mask issues caused by either poor design or installation. For example, Hawkins was instructed to investigate the collapse of a scaffold structure (which also had a scaffold roof) that had been erected over a building extension. Weather data was obtained and reviewed, coupled with an analysis of the scaffold design. The Hawkins’ investigation concluded that the wind speeds experienced were probably not what would be considered as a ‘storm’ and were instead what a scaffold should ordinarily be designed to withstand. Further, it was identified that parts of the design of the scaffold had been overlooked and these design failings had probably caused the collapse.

In another instance, a scaffold contractor installed a scaffold platform around a domestic property to enable repairs to the main roof of the property. Part of this scaffold ‘bridged’ over an existing part of the property using scaffold beams, and these beams were supported by a fixing secured to one of the masonry walls of the property. The scaffold failure was likely to be a result of high loads (predominantly the ‘self-weight’ of the scaffold) being applied to one of the components and overloading it. The components used in the scaffold assembly were all typical, but the application of such high loads, or a lack of support in one area, is not particularly common, and therefore, a specific design should have been undertaken, but had not been.

Falling from ladders, when used purely as access, or to work from, is a common type of incident that Hawkins’ investigators regularly provide comment upon. The Health and Safety Executive (HSE) has published numerous guidance to counter the myths that ladders are not an acceptable method of access or means of working at height. However, it is generally accepted that the use of ladders needs to be carefully controlled and other means of access should be given preference unless it is unreasonable to do so.

External ladders are often used to provide temporary access to different levels of a scaffold structure on construction sites. However, it is recommended by the NASC that the use of such ladders is limited to a height of 4.7 metres. Further, the choice of this means of access needs to be measured against the frequency and duration of use, in addition to the feasibility of other access options. Such ladders should also project above the relevant scaffold platform by a reasonable amount; the NASC recommends at least one metre. Other factors also need to be considered such as weather conditions and the transportation of equipment and materials between the levels of a scaffold.

External ladder arrangements where Hawkins have investigated a fall from height.

Hawkins has also investigated allegations relating to alterations to scaffolding and the effect that those alterations might have had. In one instance, a scaffolder fell as he and his colleagues were altering a scaffold structure to suit changing site requirements. The scaffolder that fell, alleged that part of that scaffold had been altered and made unsafe by another person. Hawkins was able to review the photographic evidence and advise where there was evidence of any such alterations. Hawkins was also able to provide a significant amount of detail in relation to the functionality of scaffold couplers, how they could be loosened, and what affect that would have on the surrounding scaffold members.

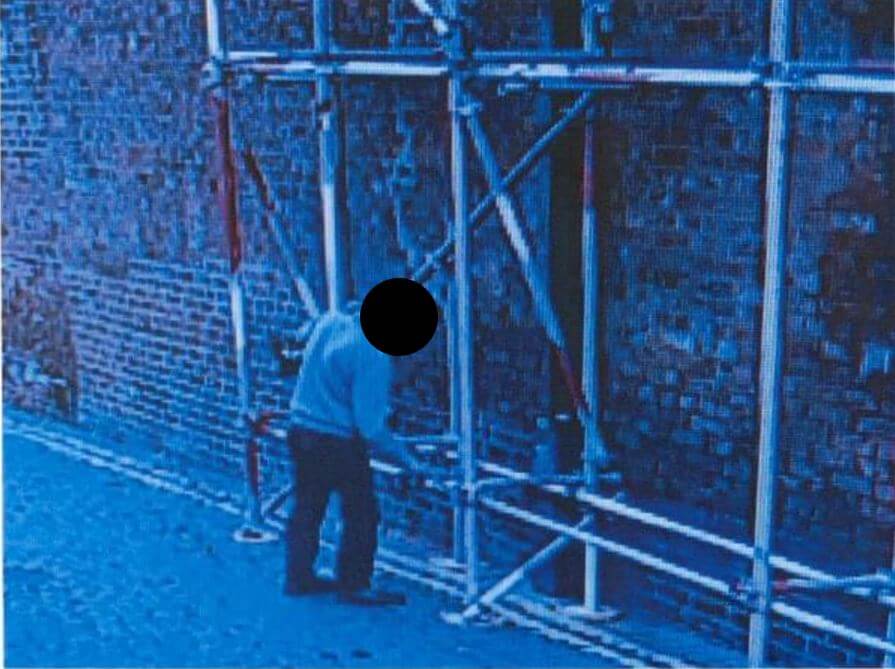

In another example, a disgruntled scaffolder, was captured on CCTV attempting to make alterations to scaffold structures, although fortunately no collapse occurred. Hawkins was asked to undertake a structural review of the relevant scaffold structures and ascertain whether the alterations made had caused the scaffold to be at risk of collapse. The analysis concluded that the modifications were very minor, and did not put the structure at risk of a collapse.

Protecting the public from construction activities, in particular during work at height, is of paramount importance. However, it should also be acknowledged that construction work still needs to be undertaken in even the busiest of places such as a city centre, where the public cannot be removed entirely from the work area. Therefore, Hawkins has also provided comment on the adequacy of means of protecting the public, including whether specific measures such as exclusion zones, scaffold protection fans and ‘brickguards’ should have been installed or not.

About the Author

Richard joined our growing Civil & Structural Engineering capability in 2017 and has led engineering investigations of a domestic and commercial nature, ranging in size from small claims to complex and large losses, including structural damage, water ingress, ground movement and catastrophic collapses. Richard also investigates personal injuries, especially construction site and other workplace accidents, including falls from height. Many of these investigations have involved providing advice on roles under the CDM Regulations, appropriate health and safety procedures and industry best practice. Richard is experienced in the legal process, having prepared reports compliant with both the Civil and Criminal Procedure Rules and has provided advice on technical engineering issues to solicitors, Counsel and in Court.