There are many dictionary definitions and meanings ascribed to the word ‘architect’. If you’ve Googled it, you might already know that. The Oxford, Cambridge and Merriam Webster dictionaries all mention design in their definitions. Two of the definitions mention construction. Only the Cambridge dictionary states that the architect “makes certain that [new buildings] are built correctly”. My emphasis added as the architect rarely has the power to ensure anything on a building project.

An architect is a qualified, registered professional. Their role is to design, support, manage and advise in the procurement of built environment projects. This broad position covers aesthetic design, technical construction, construction law, planning policy, project management and budgeting. Some architects choose to focus on one area whilst others cover all parts.

QUALIFICATION

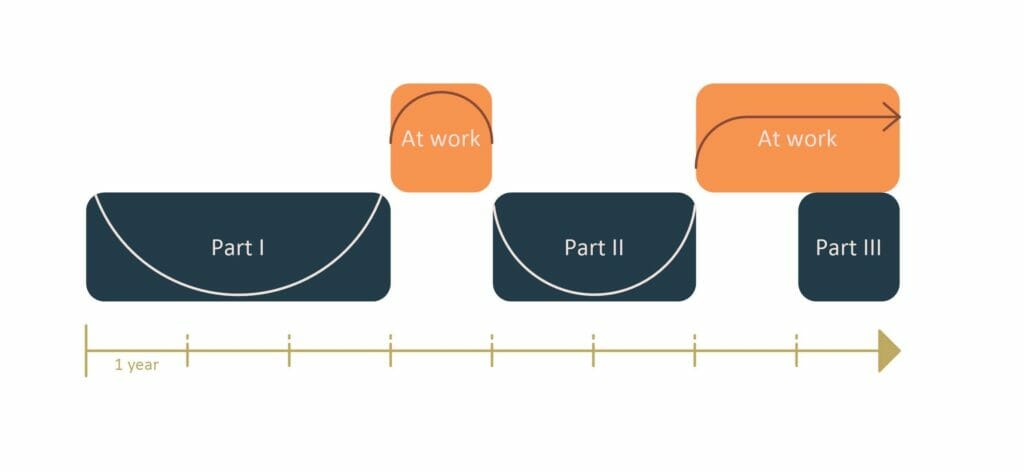

In the UK, the customary approach involves a total of 5 years study plus 2 years practical experience. The first step is a ‘standard’ three-year degree in architecture that teaches a broad range of skills including design and construction methods, theory and architectural history. This undergraduate degree is referred to as ‘Part I’.

After graduation, many architects-in-the-making (often referred to as Part 1s) take a year off studying to gain one of the two required years of practical experience in an architectural practice. This experience must be supervised by a registered architect and should provide the student with exposure to a more hands-on approach to architecture.

The second qualification is typically taught over a two-year period and is intended to build upon the student’s knowledge from Part I and practical experience. This postgraduate degree is referred to as ‘Part II’.

At this point, architects-in-the-making (referred to as Part 2s) must complete the requirement of two years practical experience under the guidance of a registered architect.

The final part of the UK based architectural student’s education is the professional examination. This exam must be completed and passed to become legally registered as an architect. The subjects taught include project management, construction law, regulations, contracts and methods of procurement. This qualification is referred to as ‘Part III’ and is intended to round off all the previous years’ experience.

This is the traditional route to qualification, but there are now multiple alternative routes offered by universities across the UK.

REGISTRATION

For someone to legally call themselves an architect they must be registered under the Architects Act 1997. It is a criminal offence to “practise or carry-on business under any name, style or title containing the word “architect” unless”[1] the person is on the Architects register, held by the Architects Registration Board (ARB).

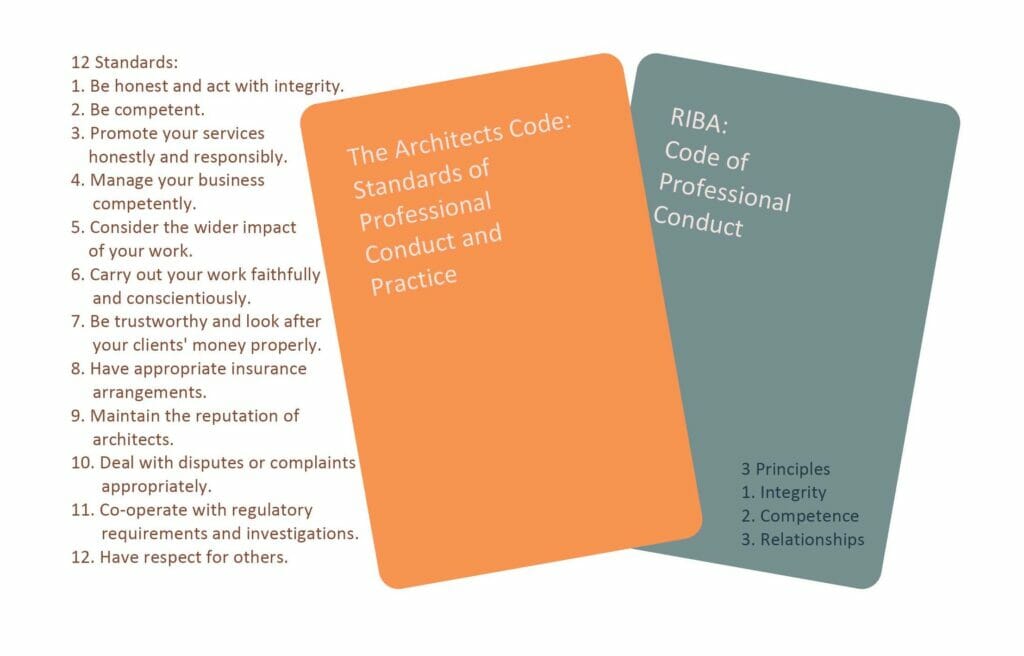

Once an architect joins the Register, they must follow the Architects Code set out by the ARB. This consists of 12 Standards of Professional Conduct and Practice which are accompanied by clauses that provide further detail. For example, Standard 12 – Have respect for others, is accompanied by a clause that specifically lists the protected characteristics that an architect must not discriminate based on. Whilst this is a clear and simple standard, others, like Standard 4 – Manage your business competently, come with multiple sub-clauses. These sub-clauses include ensuring you can provide adequate resources when entering into a contract and having a written agreement when undertaking professional work.

There are penalties for failing to abide by these codes, ranging from a warning to permanent erasure from the Register.

The ARB code was created to protect the public from architects, whilst a second code introduced by the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), is aimed at protecting the profession. The RIBA is a voluntary institution that a registered architect can choose to join and members of the RIBA are referred to as Chartered Architects. The RIBA codes focus more on sustainability and the environment, planning permission and conservation, and responsibilities as an employer. Like the ARB, there are penalties if these codes have been violated, however, there is an option for a private caution, whilst all ARB decisions are available to the public.

THE DAY JOB

It is difficult to define what an architect does because there is such variation in the profession. Setting aside the type and scale of different projects, e.g., a house extension versus a hospital, there is variation based on the construction stage, the procurement route and the architect’s appointment.

Construction Stages

Based on the RIBA plan of work, Stage 0 is when you decide you need a building and Stage 7 is the ongoing use and maintenance of that building. Therefore, Stages 1 to 6 are when the building is being designed and built – the construction stages.

The role of an architect during Stages 1 to 3 is relatively consistent regardless of procurement route or architect’s appointment. This includes undertaking site analysis, listing constraints and opportunities, helping develop the client brief through producing different options for the project, and then developing the chosen option with the input of a consultant team. At the beginning of a project, the consultant team can include a planning consultant, structural engineer, MEP (mechanical, electrical and plumbing) engineer, landscape architect, and sustainability consultant to name a few. The outcome of Stage 3 is that architectural and engineering information is spatially coordinated. If planning approval is required for the project, this is the stage where the planning application is submitted.

Stages 4 to 6 are more complicated as it does depend on the procurement route and the architect’s appointment. With the base design agreed at Stage 3, a further level of technical detail is added at Stage 4 to comply with Building Regulations, client requirements and fully coordinate with the engineering information. The outcome of Stage 4 is that all design information required to manufacture and construct the project is completed. On many projects, Stages 4 overlaps with Stage 5 to speed up the process. At Stage 5 a building contractor has been appointed by the client and the contract between them is signed. There is no design work in Stage 5 other than respond to site queries. The outcome for this stage is when manufacturing, construction and commissioning is complete. Stage 6 is when the building is handed over to the client, aftercare is initiated, and the building contract is concluded.[2]

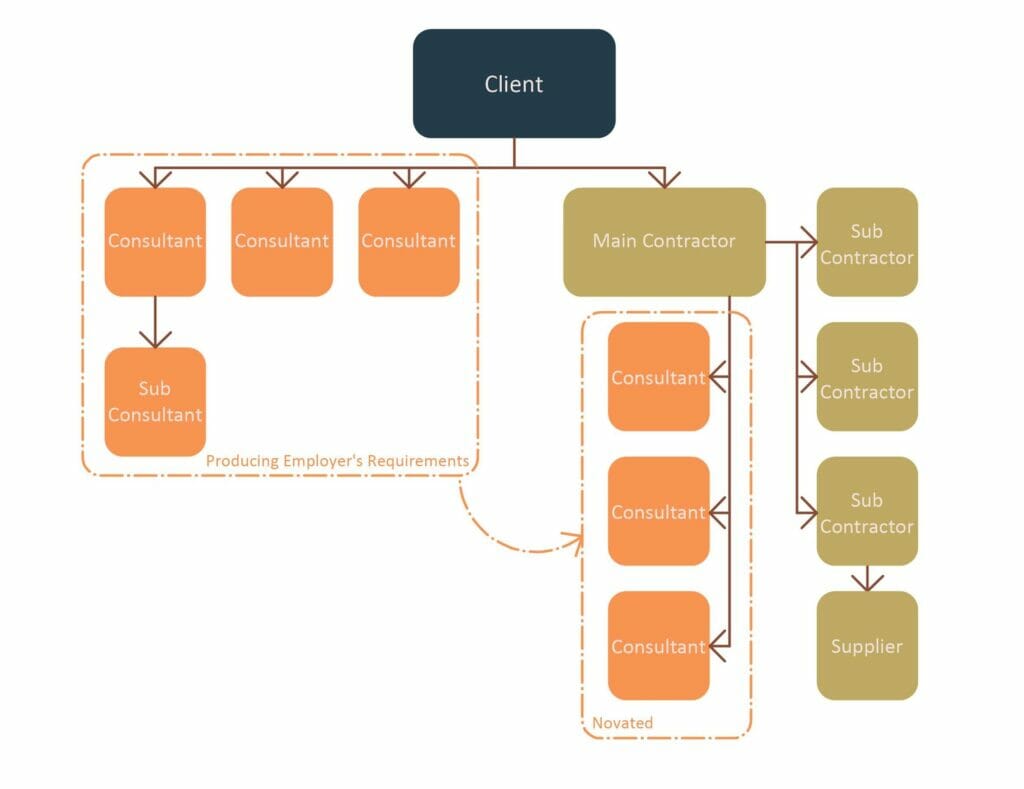

A client might only appoint an architect for Stages 1-3 or 4-6, or for the entirety of the project. Equally, an architect might be appointed for the whole project under the Client, or they may be novated at Stage 4 to the Contractor depending on the procurement route.

Procurement Routes

The term ‘procurement’ refers to the acquisition of the goods and services needed to successfully complete a build from start to finish. There are several routes that a project can take, and the long-term objectives of the client’s business plan will influence which the client chooses. The long-term objectives are categorised as time, cost, and quality. Different procurement routes are considered to deliver better on one of those aspects, sometimes two, but not all three.

Although there are an infinite variety of contractual arrangements, it is generally accepted that there are four key methods of procurement that are currently practised. In the most simplistic terms, these are:

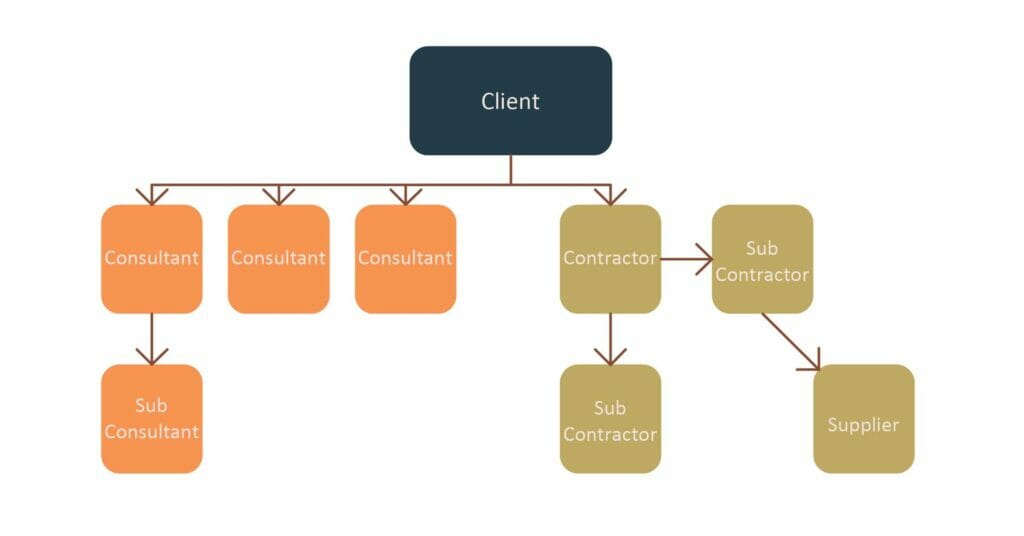

Traditional (or design-bid-build or general contracting) – the client enters into direct contractual relationships with the architect and other consultants on the one hand, and the contractor on the other. The build is based on the design of the architect and other consultants, with the contractor having no or limited design input. The client usually appoints a contract administrator who inspects the construction works and issue certificates for payment as the project progresses. This role is often taken on by the architect.

Design and Build (or design-build) – the client enters into a contract with the contractor, who takes responsibility for providing both the design and contract under a single lump sum contract. The contractor has the contractual relationships with the architect and other consultants. The client provides Employers Requirements to inform the build, and the contractor produces Contractors Proposals for any deviations.

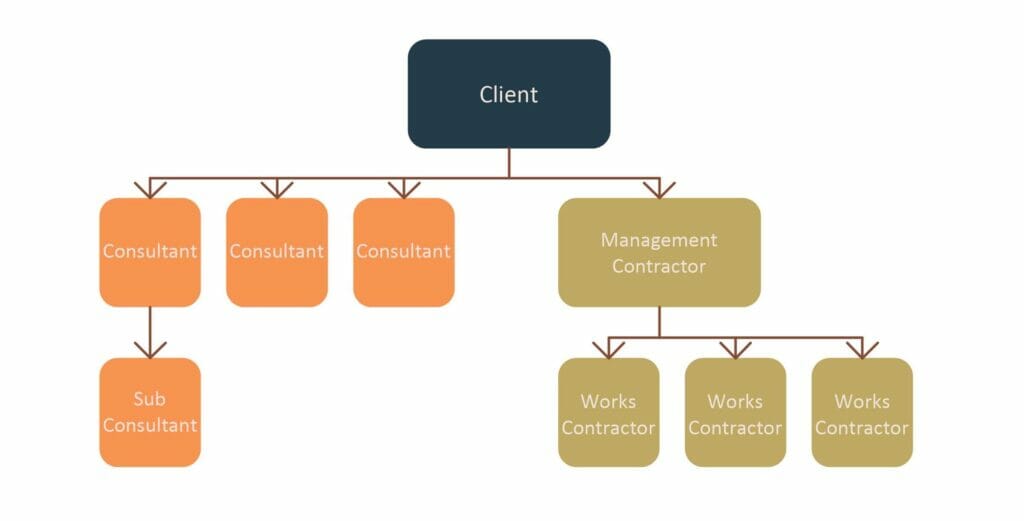

Management – the work is divided into ‘packages’ that the client lets directly with different contractors. Each package can follow either of the two above types, with all the design being carried out by a client appointed team of consultants ahead of the contractor beginning works; or where the contractor is responsible for part or all of the design of the works. This method allows construction to begin before the whole design has been completed.

Collaborative (or integrated) – the client, consultants and contractors agree to work collaboratively to achieve the defined objectives and might include sharing the risks, losses and rewards.[3]

For a more detailed explanation of these routes and more, try reading Which Contract? by Sarah Lupton and Manos Stellakis.

Scope of Appointment

There are four architectural roles on a construction job, of which an architect may perform one, several, or all. There are also further specialist roles that an architect might undertake. The scope of work that an architect has agreed to should be written into their appointment.

1. Architect / Consultant Providing Architectural Services

An architect or other consultant, such as a building surveyor, can provide architectural services during the construction stage of a project. This role includes:

- Preparing the brief with the client

- Producing a design

- Coordinating information

- Producing drawings for construction

2. Lead Designer

If the appointment includes the role of Lead Designer, additional duties could be:

- Preparing the design programme

- Developing a design responsibility matrix

- Commenting on other consultants' drawings and strategies

- Reporting to the client against the design programme

- Coordinating responses from the other consultants

3. Project Lead

Where there are many disciplines working together, the architect can also take on the role of Project Lead which can include assisting the client with:

- Determining initial construction cost

- The project programme

- The scope of other consultants' appointments

- The negotiation of other consultants' appointments

The project lead is also responsible for:

- Establishing the project management procedures

- Issuing instructions to the other consultants from the client

- Establishing a ROAD register

- Organising, chairing, and recording meetings

.4. Contract Administrator

Where the role of a contract administrator is written into the contract, such as in traditional procurement, an architect can take on this role including:

- Preparing the building contract

- Arranging for the contract to be signed and executed

- Advising the client on its duties under the contract

- Visual inspections

- Certifying interim payments

- Issuing a schedule of defective works

- Liaising with all parties

- Inspecting remedial works

- Certifying when defective works are rectified

- Assisting the client in finalising the account

- Issuing the final certificate

5. Principal Designer

One role not covered by the four architectural roles on a construction job is that of the Principal Designer (PD) as set out in the CDM regulations 2015. The PD has responsibility for coordination of health and safety during the preconstruction phase.

Regulation 5 of the CDM regulations requires the PD to:

- Be appointed by the client

- Have control of the pre-construction phase of a project

The RIBA recommends that the default choice for the Principal Designer should be the architect or consultant providing architectural services, and they should be appointed under a separate and distinct professional services contract. This recommendation is essential as the PD role will always be on a lower professional indemnity insurance cap than the architect, so care is needed that the provisions are back-to-back. In certain circumstances, the PD might have a duty to stop work on site where there is a risk to health and safety. This contradicts the architect’s duty to ensure that work keeps progressing. Stopping work as PD might therefore be a breach of the architectural appointment, hence the importance of insisting on separate appointments.

As Principal Designer duties are lengthy and confusing, many architects choose to ‘contract out’ the services to a subconsultant. However, ultimate responsibility still lies with the architect as PD.

Under a Design & Build contract, the Main Contractor becomes PD as once the architect is novated, they don’t meet either requirement of Regulation 5. Again, most contractors choose to ‘contract out’ the services back to the architect or a subconsultant, but ultimate responsibility remains with the Main Contractor.

SO WHY AREN’T NEW BUILDINGS ALWAYS ‘BUILT CORRECTLY?’

The role of an architect can be far ranging, complex, confusing, and not always fully understood by some architects themselves. Whilst this article provides descriptions of the correct ‘ideal’ scenario, parts of the construction industry may be working out of habit, with varied interpretations of the different roles and responsibilities.

Buildings, no matter how visually similar, are often built differently. And how they are different is key to working out where errors might have been made. It takes someone with specialist knowledge to unravel what happened versus what should have happened, and that often requires a Forensic Architect.

[1] Section 20 of the Architects Act 1997.

[2] RIBA Plan of Work (architecture.com)

[3] Lupton, S. and Stellakis, M. Which Contract?, 6th Edition, London: RIBA Publishing (2019)